|

The

SOEST Maile Mentoring Bridge program strives to recruit and retain Native Hawaiian and kamaʻāina undergraduates in ocean, earth and environmental science degree programs at SOEST. In May, the first cohort of Maile students--Charles "Aka" Beebe, Kanani, Lhiberty Pagaduan, and Diamond Tachera--earned bachelor's degrees with the support and encouragement of their mentors.

|

This spring, the

Jonathan Merage Foundation embarked on a long-term partnership with SOEST to explore how long-range lightning data can potentially improve storm forecasting.

"Through the ingest of lightning and storm balloon data, this project aims to increase our ability to map water vapor and heat associated with condensation of water in hurricane storm clouds in the core of the storm," said

Steven Businger, chair of the

Atmospheric Sciences Department at UHM and project lead. "In the process, details of the initial storm circulation in the hurricane model will be improved."

|

An international team of scientists led by

Pacific Biosciences Research Center researcher

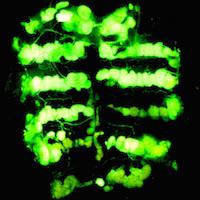

Joanne Yew may have discovered a new and effective way to control insect pests that are a threat to agriculture and humans. Yew and her team identified a gene in vinegar flies responsible for the insect's waterproof coating, which provides them with protection from microbes and environmental stress. They nicknamed the gene 'spidey.'

|

|

SOEST joins the State to educate public about sea level rise impacts and adaptation

|

|

|

|

The

International Coral Reef Symposium convened last month in Honolulu and brought together 2,500 reef scientists, policymakers and other participants from 97 nations to bridge science to policy and move from knowledge to action regarding coral reef conservation. The ongoing global coral bleaching event, which began in 2014 with a super-charged El Niño, is now the longest-lasting and largest such event ever recorded.

"What we have to do is to really translate the urgency," said

Ruth Gates, president of the International Society for Reef Studies and director of the

Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology. Gates, who helped organize the conference, said the scientific community needs to make it clear how "intimately reef health is intertwined with human health."

Bob Richmond, director of the

Kewalo Marine Laboratory and convener of the event, said the problems are very clear: "overfishing of reef herbivores and top predators, land-based sources of pollution and sedimentation, and the continued and growing impacts of climate change."

|

"The ocean is fundamental to our lives in the islands. PacIOOS strives to provide accurate and easily accessible coastal and ocean information to help improve Pacific Islanders' quality of life through empowered decision-making," said Melissa Iwamoto, director of PacIOOS. "We are pleased to continue helping island communities and authorities address both the short- and long-term challenges we face in the islands."

|

|

|

|

Image courtesy of XL Catlin Seaview Survey.

|

Scientists say good bacteria could be the key to keeping coral healthy, enable them to withstand the impacts of global warming, and secure the long-term survival of reefs worldwide.

"Healthy corals interact with complex communities of beneficial microbes or 'good bacteria'," said Tracy Ainsworth from the

ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at

James Cook University who led the study. "It is very likely that these microorganisms play a pivotal role in the capacity of coral to recover from bouts of bleaching caused by rising temperatures."

|

|

|

|

|

|