Master Class:

Saving Seed from Your Garden

|

|

Summarized by Pat Sobrero from SSE Resources

Covelo, CA, USA

As a seed saver, first your priority should be to maintain varietal purity.

Every time you grow out a variety you are creating an opportunity for genetic change to occur. In order to minimize this opportunity for change you need to consider three main factors:

plants, pollinators, and environment.

Know whether your parent plant is an open-pollinated variety or a hybrid. Save seed from open-pollinated varieties and take steps to prevent unintentional hybridization (cross-pollination) as you grow your crops.

*

An

open-pollinated

(OP) variety breeds true from seed.

*

An

heirloom

is an OP variety with a history of being preserved by an individual or a family.

*

A

hybrid

is created by crossing two different varieties of the

same species. Hybrids are not stabilized; plants grown from their seed will not resemble the parent plant. (They do not breed true.)

Know your plant's genus and species. Check your seed packet or look it up online or in a book. Plants sharing the same genus and species can cross-pollinate (hybridize) and create unexpected (and usually unwelcome) results.

*

In the squash family, acorn, delicata, spaghetti, patty pan,

yellow summer, and zucchini are all

Cucurbita pepo

and will cross-pollinate. If you grow more than one variety of

C. pepo

and do not isolate them from each other, you can't reliably predict what will grow out from seed you save.

*

Common names can be misleading, so learn your plant's

scientific name. Armenian cucumber is not a cucumber; it is a melon and will cross with some other common melons.

* A crop type can include several different species.

For

example, there are several major squash species:

maxima, moschata, argyrosperma,

and

pepo.

You can grow one variety of each and not worry about crossing.

*

The inverse is true: one species can include several crop

types: broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, collards, kohlrabi, and some kales are all the same species

(Brassica oleracea),

and will cross.

*

Vegetables may have "weedy relatives" with which they can

cross-pollinate with poor results. Carrot can cross with Queen Anne's Lace. Chicory can cross with wild chicory. Parsnip can cross with cow parsnip.

Know how your plant pollinates. Is it self-pollinating or outcrossing?

How does the pollen get from the anther (the male part of the flower) to the stigma (the female part of the flower)? Generally the more outcrossing a plant is, the higher population you need to maintain for genetic diversity and the greater the isolation distance you will need to prevent hybridization.

*

Selfers

are plants that are capable of fertilization through

self-pollination. Selfers have perfect flowers (flowers that have both male and female parts). Beans, peas, lettuce, and tomatoes are selfers. Because the chance of cross-pollination is greatly reduced, these crops are good for beginning seed savers. But there are exceptions: some cherry and some potato leaf varieties of tomato have an exerted stigma (a stigma that sticks out of the flower) and are more likely to cross than modern varieties of tomato.

*

Monoecious outcrossers

have separate female flowers and

male flowers on the same plant. An example is plants in the Cucurbitaceae family: squash, melons, and cucumbers. (In Cucurbitaceae, the female flower has a bulge at the base and sometimes the male flower looks a little more yellow because of the pollen.)

*

Dioecious outcrossers

have female plants and male plants.

Female plants have female flowers and male plants have male flowers. You need at least two plants for fertilization to occur. Spinach is dioecious.

*

Self-incompatible outcrossers

have flowers that can

only be fertilized by pollen from another plant because they reject their own DNA. Brassicas are self-incompatible outcrossers.

Of the outcrossers, beet, chard, spinach, and corn are wind- pollinated. Other outcrossers are insect-pollinated.

Know how to prevent cross-pollination by using isolation methods or by planting only one variety per species.

There are several methods of isolation you can employ so the varieties you plant don't have the opportunity to cross- pollinate with other varieties of the same species.

*

Distance

is a common method of isolation. Consult a seed-saving chart for recommended distances between different varieties of the same species, but know that distances can be affected by variables such as the numbers of pollinators, barriers, wind, etc.

*

Geography

such as stands of trees, hills, and other barriers

between your garden and another's, or between varieties of the same species on your own land can often help to minimize or prevent cross-pollination.

*

Timing

your planting so that pollen shed from one variety does not overlap with the flowering of another variety in the same species is a method of isolation.

*

Barriers

such as fine net tents can be constructed to isolate some crops. If your crop is partially self-pollinating, such as peppers, you would not need to introduce insects.

*

Hand-pollinating and bagging

are ways to prevent cross- pollination. (There are many videos on YouTube that demonstrate these techniques.) These are common ways to "isolate" both corn and squash.

Of course, planting only one variety per species or allowing only one variety per species of a biennial crop to go to seed is an excellent way to prevent cross-pollination if you don't have other gardens or farms nearby.

Know your environment.

*

Do you live in a windy area?

Beets, chard, spinach, and corn

are wind-pollinated. Open, windy locations will require 1-2 miles isolation between varieties in wind-pollinated crops.

*

Do you have many insects visiting your garden?

More insects

mean more opportunities for cross-pollination in insect- pollinated plants.

*

Know your pollen sources. What are your neighbors growing?

It can be challenging to save seed in a community garden.

Know your plant's population needs

to prevent inbreeding depression. When you are saving seed you want to harvest seed that represents the genetics of the whole population you've planted, so you'll want to save seed from a number of healthy plants. Consult a seed saving chart to learn how many plants you need. Generally, the more self-pollinating the plant is (beans, peas, tomatoes, lettuce), the smaller the population can be. The more outcrossing the plant is, the larger the population needs to be.

Know when to harvest your seeds.

*

An annual

crop requires one growing season to produce seed

and complete its life cycle. Beans, corn, squash, tomatoes, and peppers are examples of annuals.

*

A biennial

crop requires two seasons to produce seed and

complete its life cycle. Many plants we grow as annuals for food take two years to go to seed. Chard, many root vegetables, and many brassicas are biennial and must vernalize (go through a cold season) before they produce seed. You will need to grow them longer for seed than you do for food. (These plants will often take up

much

more room in your garden when they go to seed.)

*

Market maturity

is when you would harvest a crop for food.

*

Seed maturity

is when you would harvest a plant for its seed.

You don't always get to eat your plant and save its seed, too. Tomatoes are harvested for food and seed at the same time. Eggplants need to be left on the plant until large and brown to ensure the seeds are fully developed. The information about when to harvest seed from your crops can be found online or in a book on seed saving.

For more information, visit

Seed Savers Exchange has many seed saving webinars. They are a fantastic resource. We recommend:

|

|

| Webinar: Planning Your Garden for Seed Saving 2013 |

|

|

Submit Resources for Next Issue!

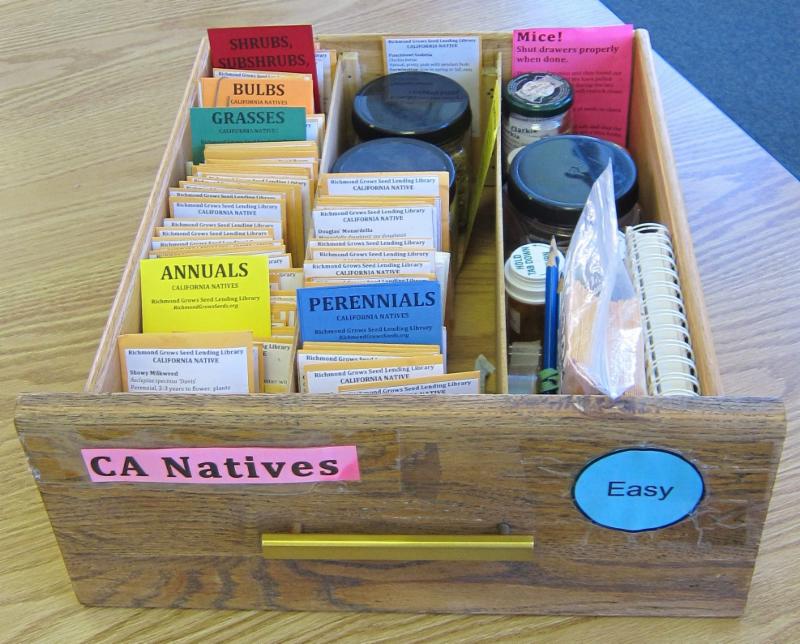

Native Gardens - June 2019 Issue

|

We'd love to share your ideas about your native seed collection.

Please include your name and the name of your seed library, town/city, province/state, and county.

|

|

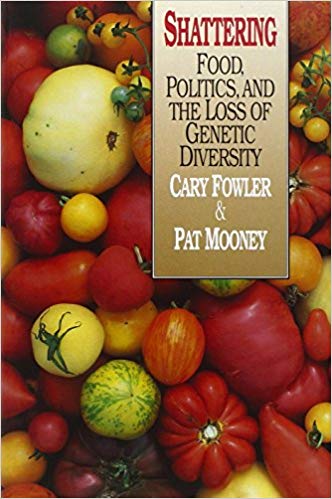

Bookworm

Sha ttering: Food, Politics, & Loss of Genetic Diversity ttering: Food, Politics, & Loss of Genetic Diversity

|

Review by Elizabeth Johnson

Written thirty years ago,

Shattering

remains a foundational look at our seed and food systems from their ancient agricultural origins to today's genetic technologies, race for resource control, and corporate politics that threaten food security for over 7 billion humans.

Wild seeds shatter when mature, bursting in all directions and hitching rides on animals and wind to find new environments to inhabit. Our early farmers worked generationally to develop non-shattering seeds that would produce larger harvests to feed growing communities.

Domesticated crops cannot survive without cultivation because they have lost many survival mechanisms.

The dance between humans and plants resulted in vast arrays of diversity over at least twelve thousand years, until the 1800s. Mendel's pea experiments opened the door to insistence on uniformity, and uniformity became the dominant mantra in plant breeding, fostering the economics of large-scale farming. Evolution and adaptability were traded for inflexible inbred plants that could only survive with major inputs of fertilizers and pesticides. Compromised plant genetics were prone to disease. Whenever new resistant germplasm was needed, breeders always returned to landraces and wild relatives to strengthen commercial varieties.

"...The future of agriculture does not depend on fancy hybrids we see in fields, but on wild species growing along fence rows, and the primitive types tended by the world's peasant farmers in centers of diversity." Genetic erosion is a global phenomenon. All seed companies, even our favorite organic seed catalogs, buy their seed supply from farmers located everywhere. Adaptability takes on new meanings in this contemporary scenario. Our most important food crops are losing diversity and "will become extinct when they lose the ability to evolve." Laboratory-made stacked-gene seeds and other genetic manipulations cannot and will never replace the complex depth, intelligence, and beauty of wild living systems.

Of the increasingly small number of seed companies controlling the majority of seed production, Fowler and Mooney list the top ten companies in 1989-none of those are on today's top four company lists. Monsanto/Bayer, Dupont, and Dow now own at least 75% of global seeds. All are chemical companies that rely on seeds bred to survive massive amounts of pesticides and fertilizers, and they have created seeds with pesticides inserted genetically into every cell. This industry's public relations continuously repeat that genetically modified organisms will be needed to feed the world and they will be the providers.

Given this dark industrial view, what are we to do? What is our responsibility now in tending our gardens and small farms? Those of us who have taken up the challenge to save endangered seeds have embarked on an adventure of our lifetimes. In 1975, Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa started person-to-person sharing, with dialog and standards to encourage gardeners to keep their favorite varieties alive. The organization is now a significant donor to its own several seed banks and to the international seed bank at Svalbard, Norway that Cary Fowler imagined and stewarded. Many other organizations and individuals followed a seed saving path that Seed Savers Exchange cleared.

Who owns the seeds that you buy? What are the company's ethics and business model? A few years ago, many seed companies -organic and conventional- started including a "Safe Seed Pledge" in their catalogs stating that agriculture depends on seeds and that they do not support or include genetically modified organisms in their inventory. Many organic farmers are encouraged to adapt plants to their unique farming systems. Many organic seed catalogs now include open-pollinated varieties that may have an opportunity to evolve with changing times and climate. Many of these O-P crops are enrolled in the OSSI, Open Source Seed Initiative, asking that anyone who uses these seeds must agree to keep the germplasm in the public commons. Many new varieties of food (and other) plants have popped up in private gardens over the years, sometimes finding their way to grocery stores.

If all the seed racks and nursery plants disappeared tomorrow, would you be able to survive? Has our personal adaptability become so clipped and curated that we no longer know how to grow what will sustain us? Is understanding of the basics of seed production in plants a foundational skill for food security?

All seed savers revel in the miracle of a seed germinating. You harvested those seeds from plants you tended. They are alive! They didn't need chemicals or PhDs to sprout. They needed US, along with care and intention, the same stuff that our long ago ancestors brought to the task.

Shattering

is an excellent foundation to consider these issues. Time has flown in the thirty years since its publication and in this current era, industrial seed production has become a behemoth controlling most of the national politics governing it. It is up to us little people to carry forward life that we treasure. No gene bank is a substitute for the ability of plants to experience change and adapt in real time. After being frozen for a hundred years, will they recognize how to live in a changed world? Wars, politics, natural disasters, and climate change may claim many important seed banks, like the arid lands seed bank in Aleppo, Syria, or the iconic Vavilov Institute in St. Petersburg.

Shattering

closes with a quote from Bentley Glass: "

We cannot turn the clock back. We cannot regain the Garden of Eden or recapture our lost innocence. From now on we are responsible for the welfare of all living things..."

This reviewer believes that Earth is, and will continue to be, the Garden of Eden, a gem in our galaxy. Seeds are the foundation of our survival on this planet. The invitation to dance in the spiral of life beckons. I'll see you in the garden where together we are responsible for the welfare of all living things.

|

|

Request for Featured Resources:

B rochures & Signages rochures & Signages

|

|

Each issue we like to feature resources for the benefit of the community. If you have brochures that we can include in our June issue to help other libraries, we would appreciate your help. We are looking for:

- Signage about seed quality

- Brochures on seed saving

Here is a

template sign we encourage you to post around the seed quality in your library:

|

Lettuce Get Involved ! !

|

|

Over the last 100 years we've lost thousands of regional seed companies and more than 90% of our commercial seed varieties.

Creating a diverse and resilient seed stock is going to happen in our communities by backyard gardens and in our seed libraries. It's been a few years since we had an active core group of people discussing resources and supporting seed libraries and local seed saving efforts. We would love to reactivate those conversations.

|

Many hands make for light work, and a few donations can keep

Cool Beans! coming to your inbox!

We are a 100% volunteer organization and all of your money will go to hosting the SeedLibraries.net website and paying for our e-subscription service for

Cool Beans! Consider becoming a sustaining at $5 a month.

Contributions are tax-deductible through Richmond Grows Seed Lending Library's fiscal agent, Urban Tilth.

|

Tips from the Fields Tips from the Fields

|

Collaborate with friends and neighbors to achieve isolation distances. It's difficult to follow the isolation guidelines in smaller gardens so having your friend grow one variety across town and you growing another one, you can swap produce and seeds while keeping them from crossing.

- Judith, Littleton Seed Library, Littleton, MA, USA |

Feedback for this issue? Ideas for the next issue? Feedback for this issue? Ideas for the next issue?

|

This Issue: Planning your Garden for Seed Saving

Do you have any tips or strategies that we missed? Do you have any questions after reading the main article that would be of benefit to other seed librarians?

Next Issue: Native Gardens (June 2019)

Do you have native plants in your garden? How do you get your collection? How do you label? Please share any tips or strategies?

Fill in this survey. Your suggestions will be included in "Tips from the Field" to benefit others.

|

|

|

Seed Saving Courses

|

August 16-18, 2019

Seed Savers Exchange, Decorah, IA, USA

Grain School

Albuquerque, NM, USA

July 26-27, 2019

Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance, Seed Broadcast & Garden's Edge

Seed School

Denver, CO, USA

October 20-25, 2019

Register

Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance & Global Seed Savers

Self-paced, online course

$97

Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance and Urban Farm

Offering a day long seed saving class?

Cool Beans! and our Facebook page.

|

|

Save the Date!

9th Annual Seed Library Summit

Sept. 11, 2019

National Heirloom Expo Santa Rosa, CA, USA

Seed Savers Exchange Conference & Campout

July 19-20, 2019

Decorah, IA, USA

Register

Offering a day long seed celebration or meeting?

We're happy to share it. Email us.

|

|

720+ Open!

Sister Seed Libraries

|

- Have you opened?

- Added branches?

- Created a website?

Check the Sister Libraries List to see if your information is accurate and to find other libraries near you. Fill in this survey to help us keep the list accurate.

|

|

Seed Libraries Association

|

- Resources on how to start & manage a seed library

- Sister Seed Libraries pages

- Inspirational projects associated with seed libraries

|

Lina Sisco Bird Egg Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

Photo by Electra de Peyster, Community Seed Exchange, Sebastopol, CA, USA

Seeds originally from Seed Savers Exchange:

"Family heirloom brought to Missouri by covered wagon in the 1880s by Lina's grandmother. Lina Sisco was one of the six original members of SSE, which was founded in 1975. Large tan bean with maroon markings. Horticultural type used as a dry bean. Bush habit, dry, 85 days." Help steward

this variety.

Do you have a banner bean photo you'd like included?

Email us. Let us know the variety, your name, location, and if you are associated with a seed project.

|

Stay Connected

|

|

|

|