How Does El Niño Influence Winter Precipitation Over

the U.S.?

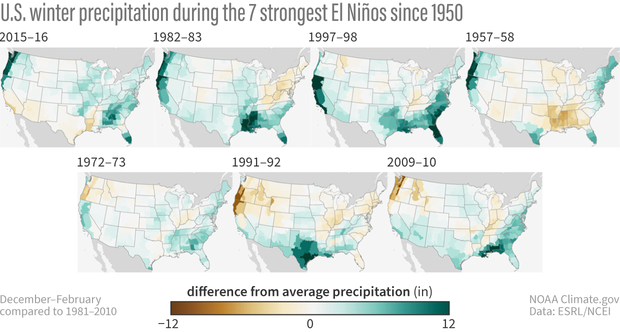

After the last three winters of La Niña conditions, the tropical Pacific is looking much different this year, with a strong El Niño likely this winter. Historically, how has El Niño shaped precipitation over the U.S.?

| |

| |

For the 7 strongest El Niño events since 1950, wetter-than-normal conditions occurred along parts of the West Coast and southern tier of the U.S., especially in the Southeast. This is expected because El Niño causes the jet stream to shift southward and extend eastward over the southern U.S., but that result is not guaranteed. For example, in the El Niño of 1957-58, much of the Southeast was actually drier than normal. Climate scientists use hundreds of modeled forecasts to predict where precipitation will fall, but these models simulate chaotic properties of nature with mathematical equations.

Although almost anything can happen in a given winter, El Niño or La Niña can tilt the odds in favor of a particular outcome, meaning that those hundreds of predictions may lean in a certain direction. Additionally, the stronger the El Niño, the more likely the U.S. winter precipitation pattern will match both the average of model forecasts and the typical El Niño precipitation pattern. Because there are higher chances in certain outcomes (e.g., a wetter winter), the presence of El Niño can help users assess risk and make plans.

| |

Snow Drought: Low Precipitation and Warm Temperatures Drive Snow Drought Risk in the West | |

Water Year 2024, which began October 1, 2023, started on the dry side for much of the West, leading to widespread snow drought conditions through the end of November. Snow drought is most prevalent in the Northern Rockies, Sierra Nevada, and parts of the southern Intermountain West. November storms in both the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range had high snow levels that contributed to warm snow drought conditions at lower elevations. A series of strong storms impacted the Pacific Northwest, northern Great Basin, and central Rockies during the first several days of December and greatly improved snowpack conditions.

Snow drought is an evolving process, not a static state. Early in the season, snow drought recovery can happen quickly following one or two heavy winter storms. Recovery from snow drought during late winter and early spring, when snowpack is typically near peak, can be more difficult due to months of low or melted snow. Learn More >

| |

Understanding the Impact of Irrigation on Historic Drought | When there is low precipitation, irrigation moistens the soil and can mitigate the impact of low precipitation on crops. But limited historic data about irrigation and agricultural drought can make it challenging to understand how past droughts impacted irrigation. Researchers at Harvard University found a new method of calculating the evaporative fraction, a ratio of changes in heat due to evaporation, which may allow drought researchers to estimate historic agricultural drought in a way that better captures the impact of irrigation. This information may allow researchers to better understand long-term changes in drought and irrigation under climate change. Learn More > | |

Drought, Wildfire Caused $11.2 Billion in Damage in West Coast States | Over the last two decades, drought and wildfire caused more than $11.2 billion in damage to privately owned timberland in Oregon, Washington, and California, according to a new study from Oregon State University. This represents a 10% reduction in the value of private timberland in these states. About half of this economic damage is attributed to climate change. “This study shows that climate change is already reducing the value of western forests,” said David Lewis, a natural resource economist at Oregon State. “This isn’t a hypothetical future effect. These are damages that have already happened because it is riskier to hold assets like timberland.” Learn More > | |

|

FEATURED MAPS + DATA

USGS Flow Photo Explorer: Predicting Streamflow From Timelapse Images Using AI

| |

Flow is a critical variable in streams since it affects aquatic and riparian ecosystems and human uses of water. Flow regimes are changing due to anthropogenic (e.g., water withdrawals) and natural impacts (e.g., extreme weather events). However, most USGS streamgages are not located in small to mid-size streams, and deploying hydrological equipment is expensive and requires specialized expertise. The Flow Photo Explorer was created to help states, tribal nations, and other entities by promoting a low-cost and user-friendly alternative with the use of continuous imagery for flow monitoring. Learn More > | |

Apply to Host a BIA WaterCorps Intern | |

The WaterCorps program’s mission is to provide high quality technical skills and internship opportunities to tribal members in the water resources field. The WaterCorps program supports enrolled tribal youth ages 18-30 (35 if a veteran) in 6-month internships at Host Sites across the country. Host Sites provide mentorship, training, and direct experience in water resources projects. Host Sites may be affiliated with federal, state, county, tribal, municipal, or non-profit agencies. WaterCorps members are fully funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs at no cost to the Host Site. Projects must relate to water resources and last for 26 weeks. Apply Here >

| |

NIDIS Drought Alert Emails: Get Local Drought Conditions and Outlooks in Your Inbox | |

Get automated email alerts from NIDIS when U.S. Drought Monitor conditions change for your location, or when NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center releases a new drought outlook, predicting whether drought will remain, develop, improve, or be removed. Sign Up Here >

| |

|

UPCOMING

Events & Webinars

| |

About NIDIS

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) was authorized by Congress in 2006 (Public Law 109-430) with an interagency mandate to develop and provide a national drought early warning information system, by coordinating and integrating drought research, and building upon existing federal, tribal, state, and local partnerships.

| | | | |